Addressing the Need for Representation and Diversity — in Genetic Risk Assessments

Feb 19, 2021 — Atlanta, GA

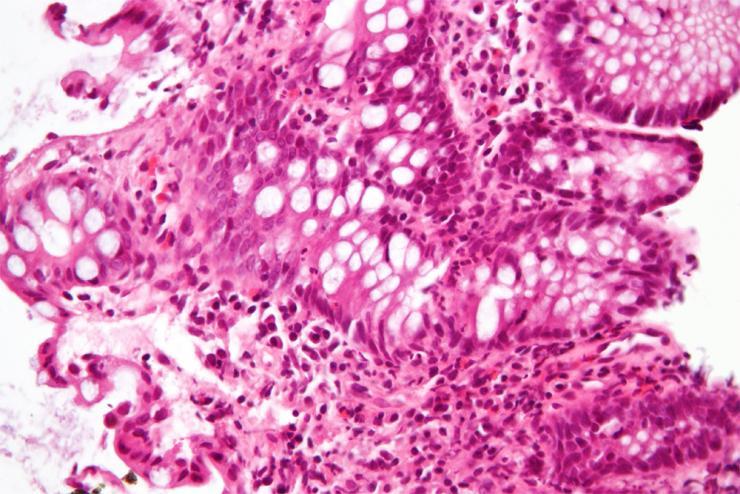

A high magnification micrograph of "cryptitis" in a case of Crohn's disease, colorized with an H&E stain and enhanced with post-processing, showing colonic biopsy of mucosa. The micrograph show neutrophils within the crypt and several eosinophils. The image alone is not a diagnostic for Crohn's disease. (Courtesy Wikimedia author Nephron)

With the sequencing of the human genome, scientists say personalized medicine is a more realistic goal. A future of customized medications, better understanding about disease factors and individualized risks, and a deeper knowledge of how cell mutations result in diseases like cancer could help pave the way for healthier populations around the globe.

But to realize this future, scientists need to build better risk assessments containing as much genetic information as possible regarding human populations — without compromising security and privacy, and without marginalizing or overrepresenting any groups. To date, existing datasets of this type of information have largely focused on individuals of European ancestry — which has meant that most people in the world have either been critically underrepresented, or at times not represented at all, among these important genomic studies and resources.

Many groups are working together to improve those datasets, including School of Biological Sciences Patton Professor Greg Gibson, who recently teamed up with Emory University School of Medicine’s Subra Kugathasan, M.D. and other colleagues to publish a new study based on what Gibson shares as the largest whole genome-sequencing study of inflammatory bowel disease for African-Americans to date.

“Whole-Genome Sequencing of African-Americans Implicates Differential Genetic Architecture in Inflammatory Bowel Disease,” published February 17 in the American Journal for Human Genetics, researches inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and Crohn’s disease in more than 3,000 Americans of African descent. IBD patients made up 1,774 members of the group, while the control group numbered 1,644 individuals without IBD.

“The huge concern in the field is that all minorities are dramatically underrepresented” in genetic studies, Gibson notes, underscoring the need for more diverse studies and highlighting his interest in pursuing the current study. “It’s comprehensive, it’s incredibly powerful and it way overperforms what came before, in terms of magnitude of accomplishment. We started three years ago, which I think is pretty amazing. There are still not many studies out there as large in terms of true genomic sequencing of population.”

The group’s work hopes to build a better understanding of potential population divergence and genetic risk of specific complex diseases like IBD — as well as identify any possible corresponding evolution of susceptibility and origins of health disparities.

To achieve this, the research group set out to further resolve the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease — and also to better define the differential genetic structure of the disease across divergent ancestries. The team notes that their resulting analyses “include many alleles that were not previously examined, in a population that remains very significantly understudied.”

So, what exactly is an allele?

A brief tutorial on alleles and genomics

Alleles are alternative forms of a gene, and they’re born from mutations. “Every person’s genome has about a million out of a billion pairs that are different,” Gibson explains. These are polymorphisms, or alleles, which are “the flavor of a gene.” When a new mutation happens, its frequency is extremely rare, but some mutations do become more common over time, and contribute ever so subtly to disease.

Most of these alleles are shared by European and African-Americans, but small differences in frequency and effect can add up — especially over several thousand of them — to real differences in risk of disease progression.

Gibson also highlights the importance of understanding and taking into account the many environmental factors that can be related to IBD and Crohn’s, such as stress, diet, access to quality nutrition, access to healthcare and preventative medicine, and even differences in socioeconomic status and opportunities that also tally up to significant health and risk disparities across divergent populations.

More diverse genomics assessments coming soon?

Gibson and Kugathasan’s research was a collaborative study involving self-identified African-American subjects recruited from five primary sites across the country: Emory University (recruited as part of the Emory African-American Inflammatory Bowel Disease Consortium), Johns Hopkins/Rutgers (recruited as part of the Multicenter African-American Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study), Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Mount Sinai Medical Center, and Washington University (recruited as part of the Centers for Common Disease Genomics network).

The study was approved by the institutional review boards at each of the participating sites and informed consent was obtained from all the participants. To protect privacy, de-identified datasets including genetic data were housed at Emory University with the approval of the local ethical board.

All DNA samples investigated in the study (a total of 3,610 before quality control) were processed and sequenced at the Broad Institute of Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology following the same protocol.

More of this needs to happen, Gibson notes, so that the real work on narrowing the gaps and differences in healthcare among a diverse spectrum of populations can begin. He adds that the African genetic structure requires complete gene sequencing for all sorts of technical reasons, making it harder than more studies of Europeans — as well as essential and well worth the effort.

“If you try to predict the onset of disease and you don’t account for ancestry differences, your assessments are just way off. In any sort of medicine, you want to be as accurate as you can. That’s why it’s so critical to include diversity in genetic studies as we progress to equitable access of all health care in all populations.”

Gibson says his next research study will deal with how genetics interacts with the other factors involved in health in underrepresented communities, such as nutrition and the impact of so-called “food deserts,” environmental issues, access to important health care, and other socio-economic indicators.

“It’s probably the most important paper I’ll ever work on,” he says.

Renay San Miguel

Communications Officer/Science Writer

College of Sciences

404-894-5209